What would happen if our lifeline—water—were cut off during a major disaster? In preparation for such emergencies, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government has established “Emergency Water Supply Stations” throughout the city. But can these stations truly deliver the “life-saving water” we need? In this article, we’ll take a closer look at their capabilities and limitations.

What Are Tokyo’s Emergency Water Supply Stations?

Tokyo’s Emergency Water Supply Stations are designated sites that provide emergency water when water service is disrupted due to a large-scale disaster such as a major earthquake. They are installed at major water treatment and distribution facilities, and are built with robust seismic-resistant structures.

You can check the locations and storage capacities of these stations via the Tokyo Waterworks Bureau website or the official Waterworks Bureau app. The stored water is regularly cycled to ensure freshness at all times.

A Shocking Calculation: How Many Days Can Your Station Cover?

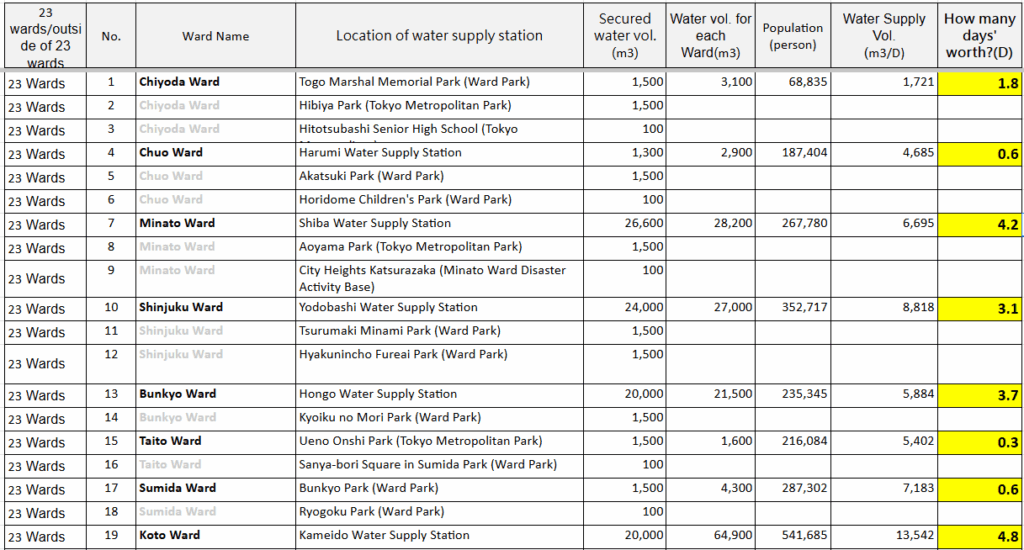

So, how many days’ worth of water is actually stored at these emergency stations?

In daily life, the average person in Tokyo uses about 250 liters of water per day. However, during a disaster, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare recommends a minimum of 25 liters per person per day to sustain basic life and health.

Using this “25 liters per person per day” standard, I ran independent calculations by comparing the published storage capacities of Tokyo’s emergency water stations with the latest 2025 population data for each ward and city.

The result? In one word: alarming.

While some wards have more storage than others, the shocking truth is that in many areas, the stored water won’t even last a day or two. And in most wards, it won’t even cover a full week.

I’ve made this calculation sheet public, so feel free to check how many days your local station can cover.

The Reality Check: Not Everyone Can Haul 25 Liters a Day

Of course, these calculations are purely theoretical.

- Access and Transport Challenges: For families living far from a water station, without proper water containers, with many members, or with elderly or disabled individuals, hauling 25 liters of water per person per day is an enormous challenge. In reality, most people will likely not be able to carry that much water.

- The “Carry Home” Limit: Even for me, with water containers and living just under 1 km from my nearest station, making daily trips on foot to fetch 25 liters is not realistic.

On the other hand, nearby residents with containers or those with vehicle access* might end up taking more than 25 liters per person per day.

Ultimately, until a real disaster strikes, it’s impossible to know how well these stations will function or how long they can continue supplying water. However, one thing is clear: their capacity is limited.

*Immediately after a major earthquake, private vehicle use inside Tokyo’s inner loop road (Kan-nana) will be restricted and gradually lifted in phases.

Lessons from Noto: The Harsh Reality of Life Without Water

I spent six months on the ground supporting disaster relief in Noto after the New Year’s Day 2024 earthquake. While I occasionally traveled back to Kanazawa City to rest, I lived under harsh conditions with almost no access to water for half a year.

Because it was winter, I wasn’t sweating much, and going two or three days without bathing wasn’t physically unbearable. But my hair became greasy, and I felt uncomfortable. By late June, just before I returned to Tokyo, the hot season had arrived, and the inconvenience of no water became even more pronounced. I realized firsthand that 25 liters per person per day is truly the bare minimum for maintaining health and basic hygiene.

Drinking water was abundant in the form of bottled water. Shelters were stocked with large supplies, and few people struggled to find something to drink.

However, I’ll never forget one elderly woman who sighed, “They say take as much as you want, but for someone like me, just carrying these bottles home is exhausting… I can’t do this every day.”

At the bathing support site I managed, many evacuees were avoiding showers. When I asked why, the answer was simple: “We’re holding off on bathing because we can’t do laundry.” This was in late March, as the weather warmed up. Even with drinking water available, poor hygiene became a serious concern.

From my experience in Noto, I strongly feel that during disasters, people struggle more with “bathing and laundry” than with drinking water.

Is Your Water Preparedness Enough?

Today, as a founder of my own company, I constantly think and act on the challenges facing Japan’s water infrastructure and disaster water management.

The Tokyo Waterworks Bureau has implemented many commendable countermeasures for earthquakes. Still, relying solely on emergency water stations won’t be enough—especially for long-term outages. As the Noto experience shows, even with enough drinking water, lack of water for daily needs can dramatically lower quality of life and even pose health risks.

Now more than ever, we need to adopt a mindset of “securing our own domestic water during disasters.”