One in every four water pipes across Japan has already exceeded its legal service life of 40 years. Replacing them all would cost a staggering 6.4 trillion yen. This estimate is based on applying Tokyo’s pipe replacement unit cost of 40 million yen/km to Japan’s 160,000 km of aging pipes that had exceeded their legal lifespan as of FY2021. Meanwhile, Japan’s population continues to decline.

Faced with this massive replacement cost and shrinking demand, it’s time to rethink the assumption that “all pipes must be replaced.” Japan’s water infrastructure needs a fundamental shift toward a more sustainable future.

1. The Harsh Reality of Aging Pipes: A Hidden Crisis

Beneath our feet, Japan’s water infrastructure is quietly deteriorating.

- Severe Aging: As of 2021, 22% of Japan’s water pipes have surpassed their legal lifespan of 40 years, according to data from the Japan Water Works Association.

- Frequent Leaks: This aging has led to 20,000 water leak incidents annually, impacting daily life and wasting precious water resources.

- Low Earthquake Resilience: Only 41% of water infrastructure is earthquake-resistant nationwide. As seen in the Noto Peninsula earthquake, large-scale disasters pose serious risks of prolonged service outages.

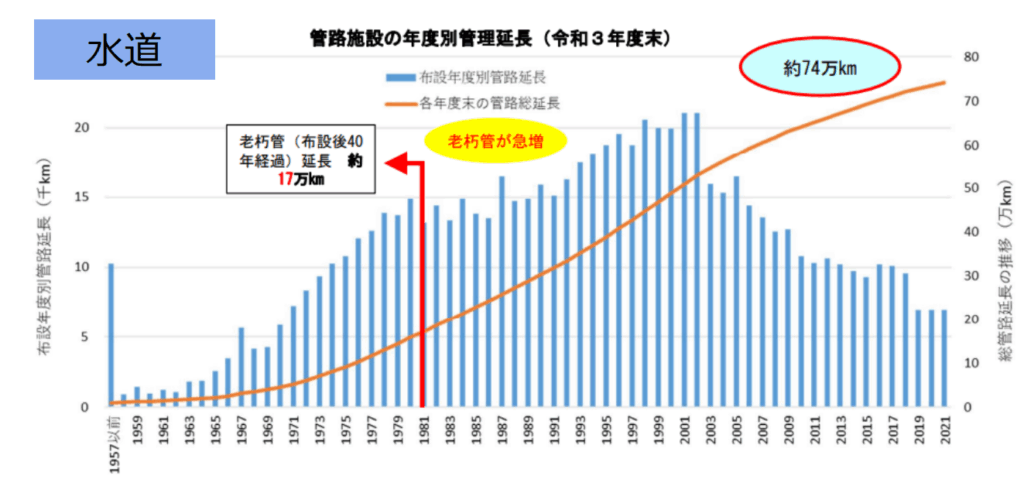

This graph shows how Japan’s water infrastructure was built rapidly during its post-war economic boom, resulting in a concentration of aging pipes today.

2. The Cost Reality: Total Replacement is Unrealistic

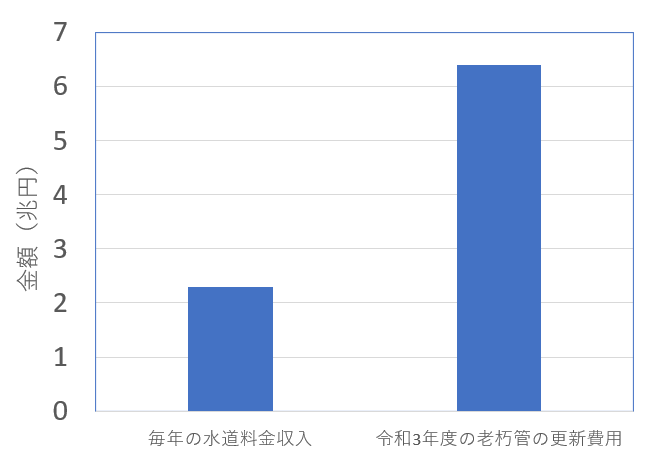

So how much would it cost to replace all the aging pipes?

With approximately 742,000 km of total pipeline length, and 22% (about 163,000 km) needing replacement, applying Tokyo’s unit cost of 40 million yen/km gives us a mind-boggling total of 6.4 trillion yen.

This 6.4 trillion yen cost is nearly three years’ worth of Japan’s total annual water utility revenue (about 2.3 trillion yen).

Given current financial conditions, replacing all aging infrastructure is physically and fiscally impossible. And as the population shrinks, per-unit costs will only increase.

3. A New Reality: Shrinking Population, Shrinking Demand

Japan’s water system was once built in line with population growth and economic expansion. But that premise has changed dramatically.

- Accelerating Population Decline: Japan’s population peaked in 2010 and is projected to decline by around 20% by 2050.

- Declining Water Demand: Water supply volume has already peaked, with a 30% drop over the past 30 years.

These changes highlight how the traditional model — assuming “ever-increasing demand” — is now outdated. Instead of replacing all legacy pipes, we must embrace a new infrastructure approach: replace only what’s necessary.

4. Rethinking Supply Areas: From Expansion to Selective Downsizing

One key strategy is reviewing service areas and downsizing the water network — not simply reducing coverage, but building a smarter, more sustainable system.

*Water service areas are regions designated by local governments for water provision under Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare approval. Under the Waterworks Act, utilities are not permitted to deny water service to residents within these areas. While the Act includes provisions for expanding service areas, it does not explicitly provide for reducing or revising them — reflecting the growth-centric assumptions of the era in which the law was written.

4-1. The Concept of Downsizing: Toward Optimization

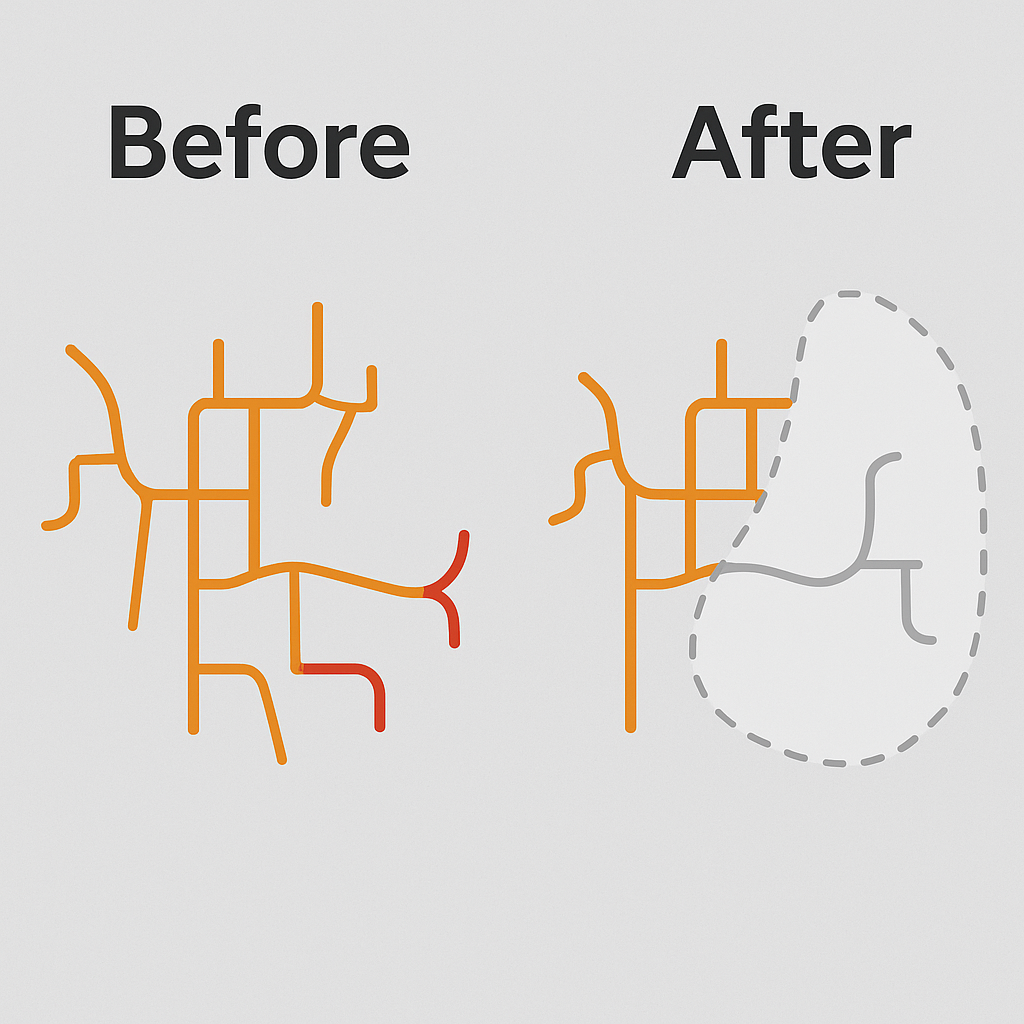

“Downsizing” means detaching areas with no residents or significant demand — such as depopulated zones or regions where industry has declined — from the main water network. This allows utilities to focus limited resources on core pipelines and densely populated areas, reducing the burden of maintaining sprawling networks.

Case Study: Toyota City’s Water Service Area Reform

In Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture, authorities are actively planning for population decline by preparing to “downsize” service areas. Their restructuring plan targets sparsely populated mountain areas with low profitability, with a clear strategy to rationalize these regions.

One initiative involves limiting service areas to within 100 meters of existing pipelines. This approach reduces inefficient terminal maintenance costs and reallocates resources to higher-need regions. As a result, Toyota City’s service area will shrink from 568 km² to 345 km² — a reduction of 223 km². Importantly, this includes plans for alternative services such as water delivery trucks to maintain access in affected areas.

4-2. Pipe Material Reform: Resilience and Cost Reduction

Alongside network optimization, changing the types of pipes used is a key way to cut costs. Traditional pipes have relied on ductile iron, but moving beyond this one-size-fits-all approach is crucial.

- Promoting HDPE Pipes: High-density polyethylene (HDPE) pipes offer excellent flexibility and earthquake resistance, and they are also relatively low-cost — a combination that helps reduce both capital and maintenance expenses.

- Case Example: Several municipalities are already adopting HDPE pipes, enabling them to build more quake-resistant networks while reducing costs — an effective strategy for tackling aging infrastructure and seismic risk simultaneously.

This diagram represents the “downsizing” concept: not expanding blindly, but selectively removing underused segments and reinforcing the rest for efficiency and resilience.

5. Other Options (Overview)

Beyond downsizing service areas, other innovative strategies are emerging to address Japan’s water infrastructure challenges. We’ll explore these in future articles, but here’s a brief overview:

- Localized Supply Systems: Rather than relying on massive central treatment plants, multiple small-scale systems can serve localized areas — improving resilience and adapting to local needs.

- Automated Tanker Water Delivery: For disconnected or remote areas, water delivery via automated tankers is being considered as a future solution.

- New Water Treatment Methods: Advanced technologies like ultrafiltration/microfiltration membranes and biosand filtration offer high-quality water at lower cost than traditional rapid filtration.

6. Legal Barriers & Government Action: Toward National Downsizing Guidelines

Japan’s Waterworks Act and associated regulations were designed with expansion in mind. As such, reducing service areas or adjusting service levels faces significant legal hurdles.

To address this, engineers and policymakers have been quietly working on institutional reforms. A joint working group from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and MLIT is now developing national guidelines for “downsizing” water systems by FY2025. This marks a pivotal step toward reshaping Japan’s water future.

7. Summary & What’s Next

It’s time to move beyond the outdated mindset of “replace everything.” Instead, Japan’s water utilities must prioritize, adapt, and protect what truly matters. This shift is not a sign of decline — it’s the first step toward sustainable, community-tailored water services.

In the next article, we’ll explore “how to manage multiple water supply zones within a single service area” and how this can strengthen resilience and efficiency in disaster-prone regions.

> Share your thoughts! Tell us about your region’s aging water pipes or leave feedback on this article in the comments.