In the previous article, we introduced the initiatives of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Waterworks in preparation for earthquakes.

Comprehensive measures have been taken to prepare for the possibility of a future major earthquake striking directly beneath the Tokyo metropolitan area. Nevertheless, should such a quake occur, it is still possible that damage or disruptions to the water supply could arise.

This time, we would like to explore with you what could happen under such dire circumstances.

Our Greatest Supporters May Also Be Victims

A major earthquake strikes directly beneath the capital.

In that instant, 30 million people in the Tokyo metropolitan area become disaster victims at once.

This includes not only those whose homes or workplaces are physically damaged (primary victims), but also those whose daily lives are disrupted due to outages of electricity, gas, and water (secondary victims). In short, nearly everyone residing in the Tokyo area would be considered affected.

Among the secondary victims, it is only natural that some people—such as those with small children or elderly family members—may not be able to go to work as usual in order to care for their loved ones. Even in an emergency, it is unreasonable to expect these individuals to take on the role of “support personnel,” as emergencies make it all the more difficult to fulfill such roles.

Under these conditions, even recovery work that would normally be completed in a day could take two or three days due to the lack of available personnel.

In a Tokyo metropolitan earthquake, we must understand first and foremost that the majority of those providing support to disaster victims are themselves victims who return home to scenes of devastation.

Roads: Blocked, Congested, and Out of Fuel

When a magnitude 6 lower or stronger earthquake hits, such as a major one directly beneath the capital, roads in Tokyo are automatically subject to “Primary Traffic Regulation.” For detailed information, please refer to the National Police Agency’s website (link), but the most relevant points for this article are as follows:

- Vehicles will be prohibited from entering the area inside Tokyo’s Ring Road No. 7 from outside.

- Within Ring Road No. 7, only authorized vehicles will be allowed; all general vehicles will be prohibited from passing through.

- Seven major arterial roads will be designated as “Emergency Vehicle Only Routes”, allowing access only for medical vehicles, construction machinery, and their transport vehicles.

After a certain point, the “Primary Traffic Regulation” will shift into the “Secondary Traffic Regulation” phase. The following outlines the regulations and permitted vehicles during this stage:

- Only pre-authorized vehicles will be allowed to enter the area inside Ring Road No. 7 from outside.

- The seven major arterial roads will remain “Emergency Routes” restricted to medical vehicles and construction machinery (including transport vehicles).

- On general roads within Ring Road No. 7 (excluding emergency routes), general vehicles will be permitted.

The term “authorized vehicles” refers to those that have obtained prior approval with a clearly defined purpose before the disaster occurs. Approval is not granted to just anyone upon request.

That said, it’s unrealistic to expect that all vehicles involved in infrastructure recovery will have secured such prior authorization. Recovery work involves not just construction companies but also trading firms supplying materials, logistics companies transporting them, equipment rental services, and gas stations providing fuel—spanning many industries.

If these vehicles cannot move freely, then infrastructure recovery itself will inevitably be delayed.

We must acknowledge that such road conditions can further delay post-disaster recovery efforts.

Recovery That Doesn’t Go as Planned

Even under normal conditions, restoring suddenly malfunctioning infrastructure—including the arrangements for materials and coordination across sectors—can take anywhere from a few weeks to two or three months.

Following a major earthquake in the capital, it is unlikely that repair work will proceed any faster. On the contrary, we must expect longer delays due to factors such as labor shortages, communication breakdowns, and traffic gridlock hampering the delivery of supplies. It may take two to three times longer—or more—than usual to restore services.

Sewer Damage Could Render Water Supply Unusable

Even if the water supply infrastructure withstands an earthquake thanks to the efforts of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Waterworks, there are still scenarios in which water might become unusable due to other factors.

Some of you may recall the news from Yashio City in Saitama Prefecture, where a collapsed road caused by damaged sewer pipes led authorities to urge local residents to refrain from using tap water.

There have been multiple past instances where sewer system failures led to water supply disruptions.

For example, during the torrential rains that struck eastern Japan in 2019, the “Cleanpia Chikuma” wastewater treatment facility in Nagano City experienced catastrophic failure. Its underground control systems were flooded, leaving the city unable to use tap water for several months.

Around the same time in Tokyo, a luxury apartment building in Musashi-Kosugi suffered underground flooding, disabling both the water supply and elevators. The incident shocked many and raised awareness of a new form of urban disaster.

In the event of a major earthquake directly beneath the capital, sewer treatment plants could lose function due to ground shaking or liquefaction, causing manholes to rise and pipelines to break. As a result, even intact water infrastructure could become unusable.

Emergency Water Supply Stations During Disasters

If a disaster renders the water supply unusable in Tokyo, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Waterworks has established “Emergency Water Supply Stations” across the city to ensure that residents can still access drinking water.

These Emergency Water Supply Stations can be located through the official Tokyo Disaster Prevention Map or the Tokyo Waterworks Bureau’s smartphone app.

Currently, these Emergency Water Supply Stations include:

- 104 locations within the 23 wards (669,280 m³)

- 108 locations outside the 23 wards (388,380 m³) *Some not managed directly by the Bureau

This brings the total secured water volume to 1,057,660 m³.

Excluding dedicated water facilities such as purification plants (with capacity exceeding 10,000 m³ per day), the specialized Emergency Water Supply Stations are equipped with tanks of either 1,500 m³ or 100 m³ for disaster use only.

For example, in Toshima Ward, where the author resides, the situation is as follows:

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Population (2024) | 289,000 people |

| Required daily water (20 L/person/day*) | 5,800 m³/day |

| Station water storage | 2 locations with a total of 1,600 m³ (1,500 m³ + 100 m³) |

| Shortage | 4,200 m³ |

*Based on the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s Guidelines on Earthquake-Resilient Water Supply Planning (2015.6), p.21 Table 3

In other words, the Emergency Water Supply Stations in Toshima Ward would run out of water in less than a day.

In contrast, neighboring Itabashi Ward, equipped with a purification plant and dedicated supply facilities, has a secured water volume of 57,100 m³.

In central Tokyo especially, where most households do not own cars, residents would be forced to walk to the nearest water station. If those stations run dry, there may be no alternative.

Water Tanker Refills for Depleted Stations: In Theory

According to disaster response plans, water tankers are supposed to refill Emergency Water Supply Stations when they run out of water.

A standard 4-ton water tanker can transport approximately 4.0 m³ of water per trip. Refilling the 1,600 m³ of storage at Toshima Ward’s two water stations would therefore require a total of 400 tanker deliveries.

However, the total number of water tankers available across the entire country is only around 1,300.

Even if the majority of those tankers were concentrated in Tokyo after a major earthquake—say, around 400 vehicles—it would be just barely enough to refill Toshima Ward’s two stations once.

Furthermore, as previously mentioned, massive traffic congestion, fuel shortages, and the lack of personnel to operate 400 tankers raise serious doubts about whether refilling depleted water stations would actually be feasible.

(Can we realistically imagine 400 water tankers lining up at a single water station to deliver water?)

Water Tanker Dispatch Priorities (According to the Tokyo Waterworks Bureau’s Disaster Response Plan)

The order in which water tankers distribute water during an emergency is specified as follows (from the 2024 Business Plan, Chapter 3, Section 2: Earthquake Response Measures, p.79):

| Priority | Destination | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Core hospitals, central government offices | To sustain lives and government functions |

| 2 | Emergency Water Supply Stations | To provide water for the general public |

| 3 | Evacuation shelters (depending on water scarcity) | To provide water for the general public |

| Other | Major stations and key facilities | As determined necessary |

Although not mentioned in the official documents, it is reasonable to assume that the Imperial Palace and the Imperial Family would fall under Priority 1. If water tankers from the Waterworks Bureau are insufficient, support may also come from the Self-Defense Forces or private companies. In such cases, the Self-Defense Forces would operate in coordination with the Bureau following the stated priority order, while private companies would likely focus on shelters and large parks.

Conclusion: If You Don’t Receive Water at the Station, There’s No Alternative

If, by unfortunate circumstance, the water supply to your home is cut off, your only real option will be to go to the nearest Emergency Water Supply Station to receive water.

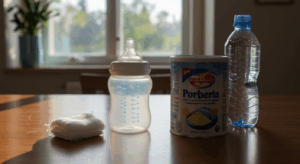

Bottled water for drinking or cooking may be distributed at nearby evacuation shelters after the disaster. However, for everyday household use, obtaining water from the Emergency Water Supply Stations will likely be essential.

That said, we will discuss in the fifth and final article of this series what options might be available if these stations run dry.

In the next installment, we will cover key points and procedures to keep in mind when collecting water from Emergency Water Supply Stations.