── Practical Water-Saving Tips for Bathing, Toilets, and Cooking ──

The average amount of water used per person per day under normal conditions is about 180 to 250 liters.

However, in the event of a disaster where the water supply is cut off, you will have to survive on just 20 liters of water per person per day until the system is restored (Guidelines for Earthquake-Resistant Water Supply Plans, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, June 2015, Table 3, p.21).

How you allocate this 20 liters across your daily needs becomes critical.

This article is based on my experience living for six months with virtually no running water while supporting recovery efforts after the Noto Earthquake. I hope to share some effective water-saving strategies.

Overview of Daily Life and Alternative Methods

Ideal Water Usage Model During Disasters

Here is one example of how to ideally allocate your daily water usage during a disaster.

| Usage Category | Normal (L) | Disaster (L) | Water-Saving Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking & Cooking | 3 | 3 | Relief supplies (bottled water) |

| Washing Dishes & Cookware | 20 | 0 | Alcohol + paper towels; use of plastic wrap or disposable plates |

| Brushing Teeth | 1 | 0 | Rinse with mouthwash or bottled water |

| Face Washing | 3 | 1 | Wet wipes |

| Hand Washing | 3 | 1 | Wet wipes, alcohol sanitizers |

| Bathing / Showering | 100 | 2 | Hair: dry shampoo; Body: special wipes or wet towels |

| Cleaning | 5 | 0 | Wet wipes, alcohol + paper towels |

| Laundry | 40 | 10~15 | — |

| Toilet | 50 | 0 | Coagulants, portable toilets, temporary toilets |

| Total | 225 | 17~22 | — |

Explanation of the Water Usage Model

Drinking & Cooking

After a major disaster, bottled water is typically delivered to affected areas as part of emergency relief efforts. These are usually distributed at shelters or relief centers. However, due to logistical delays, deliveries may take 3 to 5 days. It is advisable to store a minimum five-day supply of bottled water at home in preparation.

In our next article, we will explain methods for securing and purifying water when supplies are limited.

Washing Dishes & Cookware

Rather than using water, wipe down used dishes and cookware with paper towels and finish with alcohol. While supporting disaster recovery in Noto, I lived in a camper van and managed cooking and cleaning by wiping with paper towels soaked in alcohol and then wiping again with a fresh sheet to finish. This worked well for six months.

Surprisingly, even greasy dishes like curry pots can be kept clean with this method.

We used a large amount of alcohol for both daily life and cleaning tasks. I highly recommend keeping a 5-liter bottle at home for emergencies. Make sure it’s at least 75% alcohol by volume and clearly labeled as not safe for drinking (it contains additives to prevent ingestion).

Brushing Teeth

Brush your teeth as usual, and rinse your mouth with bottled water or mouthwash. This not only maintains hygiene but also helps prevent bad breath and gum disease. It’s a highly recommended method.

Face Washing

For the face, use body wipes to clean instead of water. Women who feel uncomfortable skipping face washing may consider masking or using a small amount of bottled water in a basin to minimize water use.

Hand Washing

Hand hygiene can be maintained by spraying alcohol and wiping with kitchen paper or using disinfectant wipes. Personally, before inserting contact lenses in the morning, I would sanitize my hands with alcohol and then rinse just my fingertips with a small amount of bottled water.

Bathing / Showering

Using Body Wipes and Dry Shampoo

Bathing was one of the most challenging issues during the Noto Earthquake relief period. As it was winter, wiping the body with special sheets was not too uncomfortable.

However, even after using dry shampoo, hair often remained sticky. While it did help a little, it wasn’t quite a substitute for a real shower. When I first tried using a wet towel, I wasn’t sure what to do with it afterward, which was another challenge.

Even just washing your hair with minimal water still takes about 1 to 1.5 liters. I recommend trying a test run at home to see how little water you can manage with to clean your entire body.

Using Public Bathhouses (Sento)

Public bathhouses may remain available even after a disaster. In Tokyo, many sento use groundwater, which can still be used if the pumping and boiler systems are functional and staff can operate them.

I once spoke with the owner of a local bathhouse who mentioned that, under the right conditions, they could continue operating using groundwater. Interestingly, they said their low price of around 500 yen per visit is sustainable only because they use groundwater, not municipal water.

JSDF Bath Services

In severely affected areas, the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) may deploy mobile bath units. During the latter half of my time in Noto, I had the opportunity to use one.

The setup is like a regular bathhouse, with a changing area in the front and a bath and washing area in the back. It was incredibly refreshing, though the wait time could easily exceed an hour during peak demand. As a support worker rather than a victim, I refrained from using it daily, limiting myself to once every three or four days.

Cleaning

When cleaning dusty or muddy interiors of damaged homes, water would be helpful—but using large wet wipes or alcohol + kitchen paper can serve as effective substitutes. This approach is ideal for saving water while maintaining hygiene.

Laundry

Laundry was honestly the most challenging part. During relief efforts in Noto, I heard more complaints about laundry than bathing. People often had to wait 5 to 8 hours just to use the limited number of mobile laundromats provided by local governments.

Some evacuees chose not to use the available bathing services simply because they hadn’t been able to wash their clothes. Clean clothes were a higher priority for them.

Laundry consumes the most water. A typical cycle of “wash → rinse 1 → rinse 2” for a 40L load requires around 120 liters of water in total (40L x 3).

If you’re fetching 20 liters per trip from a water station, doing laundry means six round-trips, which is hardly realistic. Even after one wash, you’ll need to do laundry again in two or three days.

During the Noto relief work, we experimented with purifying laundry wastewater (as part of our water treatment mission), but the results were not successful.

In the event of a major Tokyo earthquake, I believe there are three viable options for doing laundry:

1. Use Coin Laundries That Rely on Groundwater

Many public bathhouses are equipped with coin laundries, and if they use groundwater as a source, you might be able to use them even during a disaster. Expect them to be crowded, but they are a viable option.

2. Do Laundry in Areas with Water Access

Just like we traveled to Kanazawa during the Noto relief period to wash clothes and bathe, you may need to go to an area with running water. This, however, depends on transportation availability, financial resources, and time.

3. Use Laundry Support Services

Some groups during the Noto Earthquake offered volunteer or low-cost laundry services. If such a service appears in your area, it can be a lifesaver. However, beware of scams, which unfortunately increase during disasters—so use such services cautiously.

4. Use Specialized Detergents That Require No Rinsing

We discovered a product called “Umi e (To the Sea)” during our Noto mission. It allows you to finish washing with just the “wash” step—no rinsing needed. I used it multiple times, and it cleaned well without leaving odors. It even had a nice bergamot scent.

We also used this product during wastewater purification trials, and it placed significantly less burden on filtration media compared to regular detergents. If everyone used this product, water treatment would be much easier. While it is somewhat more expensive, the cost per wash is about 60 yen for a 40L load—well worth it in a disaster when water is scarce.

Instead of needing 120 liters for washing and rinsing, this detergent lets you get by with just 40 liters. If you can collect and conserve water daily, it could be a very practical solution. I personally keep a bottle as part of my emergency supplies.

5. Use Our Company’s Services (Currently in Proposal Stage)

We are currently proposing a disaster-response laundry service to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government using our company’s water purification systems. If approved, this could enable laundry access at major parks across the city during emergencies.

Toilet

Toilets consume a significant amount of water per flush. You can reduce water usage by preparing solidifying agents and using black plastic bags to handle waste. These can be used with regular toilet bowls or with portable emergency toilet kits that can be assembled when needed.

If temporary toilets are installed nearby, using those as much as possible is another option.

Flush toilets, even in water-saving mode, can use 4 liters per flush, and normal modes may use 10 to 12 liters. By using coagulants or switching to temporary toilets, you can save a considerable amount of water.

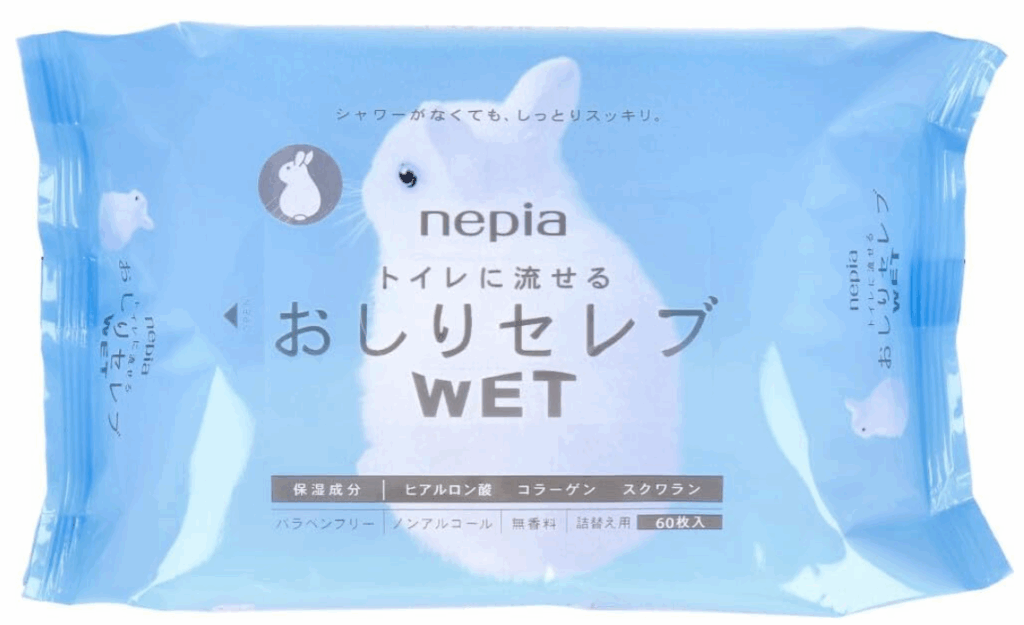

On a side note, one thing I found absolutely essential during the Noto Earthquake was wet wipes as a substitute for bidets. In unsanitary conditions with limited access to bathing, it is especially important to keep intimate areas clean. Flushable wipes are particularly useful, as they can be discarded easily.

Conclusion

Even if you’re used to relying on water for your daily needs, you’ll be surprised how well you can manage with little or none when necessary.

Laundry remains the most water-intensive task, and therefore the most challenging.

For bathing, local public bathhouses may be a vital lifeline during disasters. It’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with your local sento and ask if they use groundwater—it might come in handy someday.