The 2019 amendment of Japan’s Water Supply Act and the 25-year concession deal in Hamamatsu City have shaken the long-standing assumption that “water is a public good.” With a history of water conflicts and the global debate on privatization, now is the time to deeply reflect on the future of water infrastructure — a true lifeline for society.

Introduction: The Essence of Water as Basic Infrastructure

Water sustains our lives and underpins every industry, disaster response, hygiene system, and urban function — it is the “lifeblood of society.” In today’s modern life, if the water supply were disrupted for even a day, our way of living would collapse. In Japan, each person uses approximately 200 liters of water daily, and 90% of urban activity depends on public water supply — facts that powerfully underscore its importance.

And yet, how much do we truly understand the vast system that supports our access to “safe water at the turn of a tap,” the costs involved, and the challenges we face for the future?

1. The Ongoing Struggle Over Water: “Water Wars” Around the World

Throughout history, human civilization has developed around access to water, often fighting for its control. Securing water has always been essential for food, land cultivation, and urban growth.

Even today, “water wars” are not just relics of the past. As climate change intensifies water scarcity, and demand rises in developing nations, conflicts over water — including privatization by corporations — continue to unfold across the globe.

For example, in the Mekong River basin, upstream development by certain countries has caused tensions with downstream nations. Singapore, which long relied on water imports from neighboring Malaysia, is now working to achieve water independence through the “NEWater” project — recycling wastewater — and the construction of desalination plants. These examples show how access to water has become a core issue of national security — the reality of modern-day water conflicts.

2. Singapore’s Water Self-Sufficiency: Reducing External Dependence

Singapore faces severe geographical constraints, with limited natural water sources. For years, it depended heavily on water imports from Malaysia — a major diplomatic vulnerability.

In response, Singapore adopted a national strategy to become water self-sufficient. The core of this plan is “NEWater,” a high-tech wastewater recycling program. By 2005, NEWater was supplying nearly 30% of Singapore’s water needs. The long-term goal is to boost self-reliance as water agreements with Malaysia expire by 2060.

The country is also expanding desalination plants and implementing a “Four National Taps” strategy to diversify water sources. This reflects Singapore’s strong determination to ensure national stability and development through water independence.

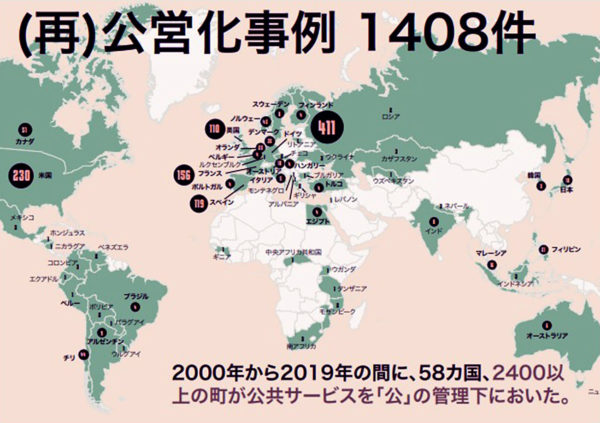

3. Privatization vs. Re-Municipalization: A Global Wave

Water utility privatization has been hotly debated worldwide, leading to a growing counter-movement of “re-municipalization.” Proponents of privatization argued that private-sector expertise and efficiency would enhance service quality and cut costs.

However, in reality, multinationals like France’s Veolia and Suez faced backlash over rising prices, degraded service, and lack of infrastructure investment. Profit-driven management often took priority over maintaining reliable public services — harming residents.

As a result, cities like Paris and Berlin that once embraced privatization have now returned to public control through re-municipalization. These cases underscore the critical lesson that water, as a public good, should not be subject solely to market forces.

4. A Turning Point in Japan: What the 2019 Water Supply Act Revision Means

In Japan, the 2019 revision of the Water Supply Act enabled municipalities to adopt the “concession model,” where operational rights of water utilities can be transferred to private companies. The intent was to stabilize operations and renew aging infrastructure.

However, this change sparked major concerns — especially the dilemma of “private investment for aging pipes vs. abandonment of rural areas.” Private firms tend to focus on profitable urban zones, potentially worsening conditions in depopulated or aging rural communities.

Critics also questioned the legislative process, pointing to external pressure from foreign firms and rushed deliberation. Despite the enormous implications for Japan’s water future, public discussion was notably lacking.

5. Hamamatsu’s 25-Year Concession: Hopes and Concerns

Hamamatsu City in Shizuoka Prefecture was the first to adopt a concession model after the legal revision. It sold the operational rights of its integrated water and sewer system to a consortium led by Veolia Japan for 25 years.

This move was driven by falling water demand due to population decline and the need for large-scale facility upgrades. The city expected private-sector expertise to enhance efficiency and secure stable investment.

Nonetheless, concerns have emerged over “lack of transparency in how concession fees are used,” “risks of rate hikes,” and “uncertainty over accountability during system failures.” For citizens, how water rates may change in the future remains a critical issue.

6. The Dilemma of Public Service vs. Profit: Echoes from Japan’s Postal Privatization

The privatization of water services highlights a core dilemma — public interest versus private profit. During Prime Minister Koizumi’s era, the postal system was privatized under the slogan “From Government to Private Sector.” The goal was to enhance efficiency and competition.

Yet postal reform didn’t yield all the expected benefits. In rural areas, postal offices played essential roles in the community — a “public value” that could not be measured purely in profit terms. Many feared this was being lost.

The same logic applies to water. For private companies, profit is the natural goal. However, water supports life, health, and social stability — it is the most essential infrastructure. Many argue it should not be commercialized. How we reconcile this dilemma and develop a sustainable water system is a pressing challenge.

7. Water Is the Land’s Inheritance — Three Principles to Uphold

Water services are not merely a utility — they are a shared inheritance of the local community. To preserve this vital asset and pass it on to future generations, we propose the following three principles:

- Universal Access to Safe and Affordable Water: Everyone, everywhere, should have access to safe water at a reasonable cost. No one should be cut off or overcharged due to geography or economic hardship.

- Local Sovereignty: Water services must reflect the will of the community. Transparent disclosure and systems for public participation are essential.

- Return of Profits to the Community: If private firms profit from water services, those profits must be reinvested in the community — such as through environmental protection and infrastructure upgrades.

“What do you think about water privatization?” We hope this question inspires each of us to reflect deeply on the future of water and take action.

Conclusion

Water is irreplaceable infrastructure — supporting our lives and social systems. The global realities of water conflicts and the trend toward (and away from) privatization remind us how vital it is to treat water as a public good.

Japan’s revised Water Supply Act and Hamamatsu’s concession mark a new era. But we must look beyond short-term efficiency. Principles such as universal access to safe and affordable water, local governance, and reinvestment of profits must be upheld.

The future of water lies in our awareness and actions. Let’s treat this issue as personal and work together to shape a better future.