We often take water for granted. But when an earthquake or flood disrupts the water supply, we suddenly realize just how vital it is.

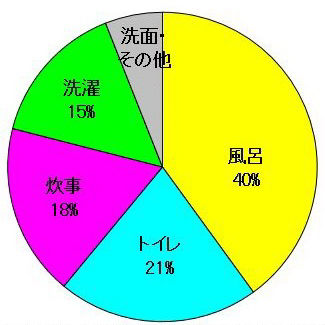

Do you know how much water people typically use each day?

Globally, the average daily water usage per person is estimated to be 250 liters. Of this, about 3 liters are used for drinking and cooking. The rest is mostly used for bathing, followed by toilet flushing, laundry, dishwashing, handwashing, and other miscellaneous tasks. Specifically, around 3 liters are used for drinking and food preparation within cooking-related activities.

Multiplying these proportions by the average daily usage of 250 liters per person gives us the following estimates for single-person, three-person, and five-person households:

| 1 Person | 3 People | 5 People | |

| Bath | 100 | 300 | 500 |

| Toilet | 52.5 | 157.5 | 262.5 |

| Cooking | 45 | 135 | 225 |

| Laundry | 37.5 | 112.5 | 162.5 |

| Washing hands/Other | 17.5 | 52.5 | 87.5 |

*All units in L/day

Required Water Amount in Emergencies

Now that we’ve estimated the amount of water needed per day, let’s imagine a disaster scenario where the water supply is cut off. How would you secure enough water to survive and maintain your daily life?

Also, which water usage categories do you think would be prioritized or reduced?

Let’s recap the daily usage amounts:

- Bath: 100L

- Toilet: 52.5L

- Cooking: 45L

- Drinking and food prep: 3L

- Washing dishes and cookware: 42L

- Laundry: 37.5L

- Washing hands/Other: 17.5L

Consider how much you could reduce each category during an emergency. Could you wipe instead of wash, or skip a day and count it as half the daily average?

Thinking through each category like this is a valuable simulation for disaster preparedness.

For reference, here’s what it looked like for me (a middle-aged man model):

- Bath: 2L (Hair: 1L, Body: 1L)

- Toilet: 10L

- Cooking: 2L (Drinking/cooking: 0L, Dishwashing: 2L)

- Laundry: 5L (Underwear: 1L, Outerwear: 4L)

- Washing hands/Other: 1L

Total: 20L

This is about as minimal as it gets. For some people, 30 or even 40 liters might be necessary. And for families, you’ll need that amount per person.

During the Noto Peninsula Earthquake, I supported local water services for six months without access to a working water supply. I’ve also experienced limited water use during overseas assignments in developing countries. Based on those experiences, I believe 20L per day is a realistic survival benchmark.

If you try to reduce further, you might need to use portable toilets instead of your home toilet, clean dishes by wiping and using alcohol spray, and rely on public bathhouses once or twice a week for both bathing and laundry. This assumes that bottled water for drinking and cooking is available from evacuation centers nearby.

In other words, even with all these measures, at least 20L per day is necessary just to maintain basic hygiene and health.

With these containers, you’ll need to fetch water from a local distribution point every day. If carrying 20L in one hand is too hard, split it into two 10L containers instead.

Still, fetching water every single day can be physically and mentally demanding. It’s important to mentally prepare for that burden as well.

Available Public Services and Facilities

If the water supply stops after a disaster, daily life becomes extremely difficult—as we’ve seen.

So, how can you get through such a situation? Let’s take a look at some useful public services and available facilities.

Bathing

Public Baths, Super Sento, and Day-use Hot Springs at Hotels or Inns

Depending on your location, nearby public baths may become accessible. If these baths use groundwater, and their boilers and facilities are not damaged or can be restored quickly, they might be usable. Many public baths also have coin laundries. Though they might be crowded, being able to bathe and do laundry at once is ideal.

Super sento (large bathhouses) or hotels may also offer day-use bathing. If you have access to transportation, visiting hot spring facilities in nearby towns can be an excellent option. In some areas, municipalities might arrange shuttle buses to hot spring facilities after a disaster.

JSDF Field Baths

In severely affected areas with no running water, the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) may deploy mobile field baths upon request from local governments to meet increased hygiene needs.

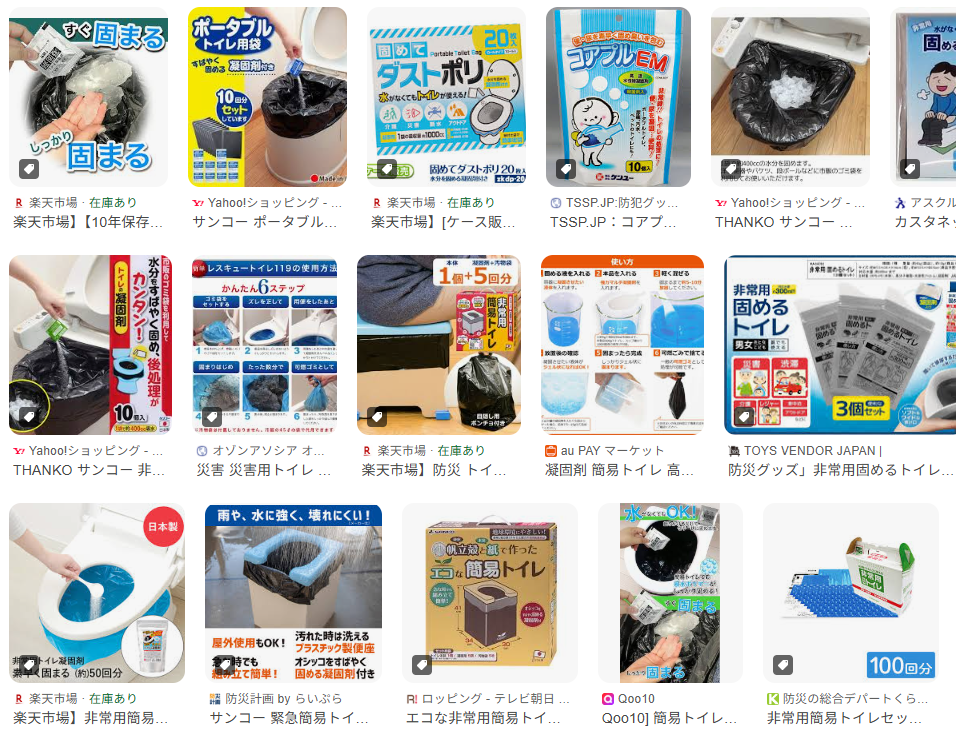

Toilets

Flushing waste with water consumes a large amount of it. If you only flush every few times, it can start to smell—especially in warm weather. In some cases, if the water supply is down, the sewer system may also be nonfunctional. In emergencies, it’s best to abandon the idea of “flush toilets” and prepare for disposal by solidifying waste instead.

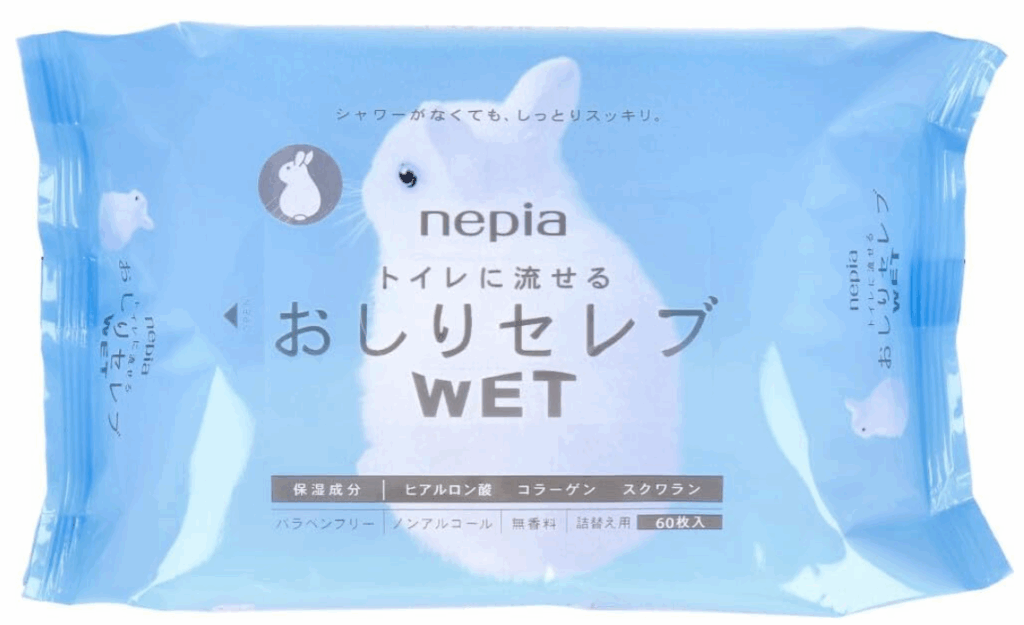

During my time in Noto, I found that after a week without bathing, personal hygiene becomes a serious issue. I personally found that flushable wet wipes—like “Oshiri Celeb”—were much more essential than body wipes. They’re gentle (alcohol-free), clean delicate areas well, and can be flushed after use. These are far more useful than regular toilet paper, especially when you’re used to a bidet and want to stay clean even in a disaster.

It’s also a good idea to take advantage of nearby portable toilets set up by local authorities or organizations. Especially in the event of a large-scale disaster in the Tokyo or Kansai area, traffic congestion may delay emergency infrastructure setup. It’s best to prepare individually or as a family ahead of time.

Drinking Water, Cooking, and Washing

Based on my experience living in Noto for six months after the disaster, bottled water, kitchen paper, and alcohol wipes were sufficient for drinking, cooking, and cleaning dishes and utensils. Drinking water—including tea and juice—usually starts arriving via emergency supply routes within three days of a disaster. If you store about 3–5 liters per person at home, that should cover the first 1–2 days for drinking and basic meals.

After the third day, you can typically rely on bottled water and supplies delivered to nearby evacuation centers.

For food, you’ll mostly eat preserved items and support rations such as bread or rice balls in the first few days. After that, you’ll gradually start cooking again. When you do, you can clean dishes and cookware by wiping them with kitchen paper or toilet paper, then finishing with alcohol spray. That alone is usually enough.

When I was supporting Noto in winter, my colleagues and I often cooked hot pot meals. Whether it was clear broth or a rich, creamy soup, wiping the pot clean worked surprisingly well—even after making curry or tonjiru (pork miso soup). Greasy dishes were no problem with this method, especially when finished with a final alcohol wipe. It really does get everything clean.

We used quite a bit of kitchen paper and alcohol spray, but it was still a small price to pay compared to the effort of fetching water for dishwashing. If you have alcohol wipes, those work just as well for the final wipe.

Laundry

Honestly, this may be the most difficult part of post-disaster life.

It’s the hardest one to fake or work around.

While providing bathing support after the Noto earthquake, I asked why fewer people than expected were using the bathing facilities. The answer I got was, “Since we can’t do laundry, we’d rather not bathe.”

People didn’t want to put on dirty clothes after getting clean, so they chose not to bathe at all.

Personally, laundry was the hardest part for me during the Noto support period.

About once every 7 to 10 days, I would stay in Kanazawa for rest and refreshment, and I’d use that time to do laundry. Still, even though I changed underwear daily, I often wore the same outerwear for 2 or 3 days straight.

If a colleague happened to be going to Kanazawa, I’d sometimes ask them to do my laundry. That happened more than just once or twice.

In disaster-hit areas like Suzu, Noto, and Wajima, the few available laundromats were packed. Some people waited 3 or 4 hours, even half a day.

Doing laundry for a whole family—rather than just yourself—is a major challenge.

Modern automatic washing machines assume running water with pressure. After a disaster, if you have to carry water home and then use it for laundry, that alone is exhausting. That’s why twin-tub (semi-automatic) washing machines were in high demand in affected areas.

In fact, I’m currently designing a system that can purify pond water from large parks like Ueno Park or Inokashira Park for laundry use—even in Tokyo. Once I finish the PR materials, I plan to propose the system to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. If it’s approved, those parks might become emergency laundry stations after a disaster.

Face Washing and Miscellaneous Uses

For face washing, body wipes or facial wipes can serve as substitutes. However, when cleaning up your home after a disaster, you’ll often find dust or mud on your hands or items—and you’ll feel the need to wash them with water. Without enough washing water, this becomes a source of stress.

Conclusion

Understanding how much water you need during a disaster is the first step toward protecting your life.

How many liters per day do you think you could manage on in your household?

We highly recommend trying a real-life simulation to find out.